How Much Freedom Did the Founders Win—If the Government Can Still Take It All?

When a Republic steals more than a King

Joseph Rivers was a 22-year-old from Romulus, Michigan, who boarded an Amtrak train in 2015 with about $16,000 in cash—his life savings—to start a new life in Los Angeles as a music video producer.

His dream was cut short when federal agents decided the government was more entitled to that cash than he was.

In Albuquerque, New Mexico, DEA agents boarded the train, questioned passengers, and asked to search his bags; Rivers agreed, and agents found the cash in a bank envelope, even calling his mother to confirm his story before stealing the money anyway under civil asset forfeiture, leaving him with no charges and no way to continue his trip or get home.

Agents later defended the robbery by citing “indicators,” like one-way tickets, routes, and large sums of cash, and emphasized that the money—not the person—was treated as “guilty,” which flipped the burden so Rivers had to fight in court to get his own savings back despite never being accused of a crime.

Rivers’ story is not unique. The ACLU documented numerous cases where people lost their property despite never being charged with crimes.

In another case, law enforcement seized a motel worth over $1.5 million based on alleged drug activity by guests—even though the owners had called police to report the activity and were actively cooperating with law enforcement.

This never would have happened to colonists living under the British Crown over 200 years ago.

When James Otis stood before the Massachusetts Superior Court on February 24, 1761, to argue against writs of assistance, he delivered what John Adams later called “the spark that lit the American Revolution.”

Otis condemned these general search warrants as “the worst instrument of arbitrary power, the most destructive of English liberty and the fundamental principles of law, that ever was found in an English law book.”

Today, our government makes those colonial-era writs look restrained by comparison. But we accept — and even defend — government theft.

Colonial Seizures: Limited Scope, Judicial Oversight

British customs enforcement in colonial America operated under constraints that don’t exist in modern civil forfeiture. Writs of assistance, while controversial, were general search warrants specifically limited to customs enforcement.

The warrants authorized customs officials to search for “prohibited and uncustomed” goods—meaning contraband and items on which duties hadn’t been paid. This was a narrow authority focused on trade enforcement, not a sweeping power to seize any property suspected of any criminal connection as it is today.

The Navigation Acts, which formed the legal foundation for these seizures, prescribed forfeiture only for violations of trade and navigation laws. The penalty was forfeiture of the smuggled goods themselves and potentially the vessel carrying them—not the seizure of unrelated property like homes, bank accounts, or personal possessions. The scope was inherently limited to items directly involved in customs violations.

But even these seizures required judicial proceedings. Judges reviewed evidence in Vice-Admiralty courts before rendering a verdict.

Property owners could contest these seizures, present evidence, and appeal a judge’s ruling.

In the end, the courts had to establish that an actual violation of law occurred before the government could permanently seize the property.

In other words, the British couldn’t simply stop a person on the road and steal their money like police can — and do — today.

It’s important to note that even with writs of assistance, enforcement of these laws was rare — especially compared to today.

And even this was enough to inspire the colonists to revolt.

Modern Civil Forfeiture: Unlimited Scope, Minimal Oversight

Approximately 80-85 percent of federal seizures result in administrative forfeitures where no one even makes a claim on the property. This doesn’t mean the seizures were legitimate—it often means the property owners can’t afford the legal fees to contest the forfeiture, which typically cost far more than the property is worth.

Today’s seizure practices make King George look like an angel. Law enforcement officers across the country can literally steal virtually any type of property as long as they suspect it has been used to commit a crime.

They don’t have to convict you.

They don’t even have to arrest you.

The mere assumption that your property was used in criminal activity is enough for government offices to seize it. It has become such a lucrative practice that civil asset forfeiture is called “policing for profit.”

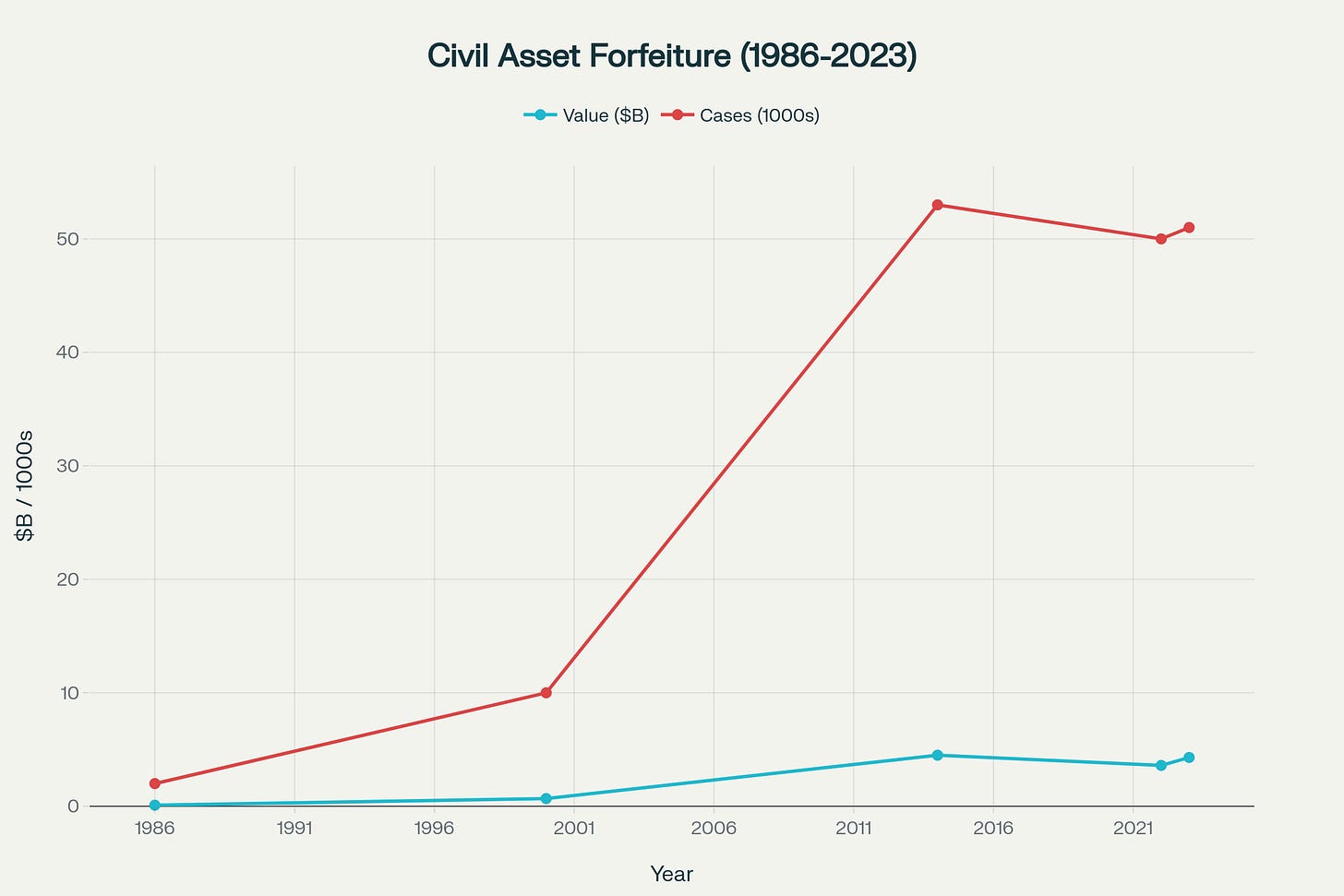

Between 2000 and 2019, the federal government alone took at least $68.8 billion in property. The Department of Justice seized over $30.8 billion, while the Treasury Department swiped nearly $15 billion.

And these figures only represent what we know—many states don’t adequately report forfeiture data, so the true total is undoubtedly higher.

The scale becomes even more shocking when examining state-level forfeitures. No-knock warrants, which enable property seizure, are executed 60,000-80,000 times annually. This means that American law enforcement conducts more property-seizure raids in a single year than the British did during the entire colonial period.

But it gets worse.

The Burden of Proof: Guilty Until Proven Innocent

After law enforcement plunders your property, getting it back is about as easy as eating an entire jar of cayenne pepper. The government doesn’t need to go through due process. It doesn’t need to show probable cause.

Once an officer assumes the property was involved in a crime, they can take it forever.

The government does not have to show that you committed a crime. Instead, the burden of proof is on you to prove your innocence.

You are guilty until proven innocent.

The Reality of Small Seizures

Those who support civil asset forfeiture often argue that it is necessary for hindering drug kingpins and organized crime. But the truth is something far different.

The practice overwhelmingly targets ordinary people for small amounts. From 2015 to 2019, half of the Department of Justice’s currency forfeitures were worth less than $12,090. At the Treasury Department, the median was just $7,320.

At the state level, the problem becomes even worse. Half of all civil forfeitures were worth less than $423. The median for Pennsylvania was $369. In Washington, DC, the median value between 2009 and 2014 was only $141.

These don’t exactly sound like major organized criminal enterprises, do they?

The Right to Be Secure

The Fourth Amendment, born directly from colonial experience with writs of assistance, declares that people have “the right to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures.”

Massachusetts went even further in 1780, declaring that “[e]very subject has a right to be secure from all unreasonable searches and seizures of his person, his house, his papers, and all his possessions.”

Modern civil forfeiture makes a mockery of these protections.

When law enforcement can steal your car because they claim they smell marijuana, steal your cash because you’re carrying “too much” for a traffic stop, or steal your motel because guests supposedly committed crimes you reported to police, you are not secure in your property.

The government we live under today is far more oppressive than the one that inspired the colonists to take up arms. Yet, we accept it. Many don’t even know these policies exist — until they fall victim to them.

It’s not all doom and gloom. Several states have made concerted efforts to reform or abolish these practices. In states like Arizona, the government is not allowed to seize property unless the owner has been convicted of a crime.

But we still have a long way to go. When government agents can steal your property on a whim, it’s impossible to argue that we live in a free country.

Government is like a vampire! It sucks our money and freedoms just so it can survive and grow.